by Rozy Bathrick

How do you know when a Greater Yellowlegs is near? It’ll tell you. These gregarious shorebirds (Tringa melanoleuca) breed in boggy forest edges in the subarctic, along the coast of the Gulf of Alaska and in central Canada. Despite their conspicuous behavior both on the breeding grounds and during migration, Greater Yellowlegs are a particularly poorly understood species. While on-the-ground observations help us understand their range and habitat use at a species-level, until this year their migration had never been tracked from a bird’s eye view. We didn’t know the routes different populations use, what stopover sites are important, how they are connected and what an individual bird’s migratory strategy looks like. Tracking data fills these gaps and informs our conservation priorities for populations.

In the muskeg bogs of the upper Cook Inlet in Alaska, Greater Yellowlegs share breeding habitat with Hudsonian Godwits, Short-billed Gulls, and Arctic Terns, rearing their chicks in small ponds between spruce stands and defending territory from treetops. In May and June of 2023, our research team, led by Nathan Senner from UMass Amherst, with support from USFWS’s Migratory Birds Division and the USGS Alaska Science Center, chased pairs of Greater Yellowlegs in the bogs and wet tundra of Beluga and King Salmon, Alaska in an effort to fill in those knowledge gaps with GPS transmitters. Using mist nets and chick-call playbacks, we captured birds during chick-rearing by carefully swiping them out of the air while they dive-bombed our heads. Easier said then done - for every successful capture there were many failures, in which birds didn't perceive us as a formidable threat, dodged the net, or lost interest in our antics. All told, we deployed GPS transmitters on 16 birds this summer, which took highly accurate locations every 1-2 days during their fall migration.

On August 1st, bird #243433 departed its breeding site in Alaska and flew nonstop across the Gulf of Alaska and down the Pacific Coast, about 1800 miles, to land in California’s Central Valley.

For a few days, it moved around agriculture fields northwest of Sacramento, then made another flight down the state to stopover near the recently-refilled Tulare Lake in Kings County.

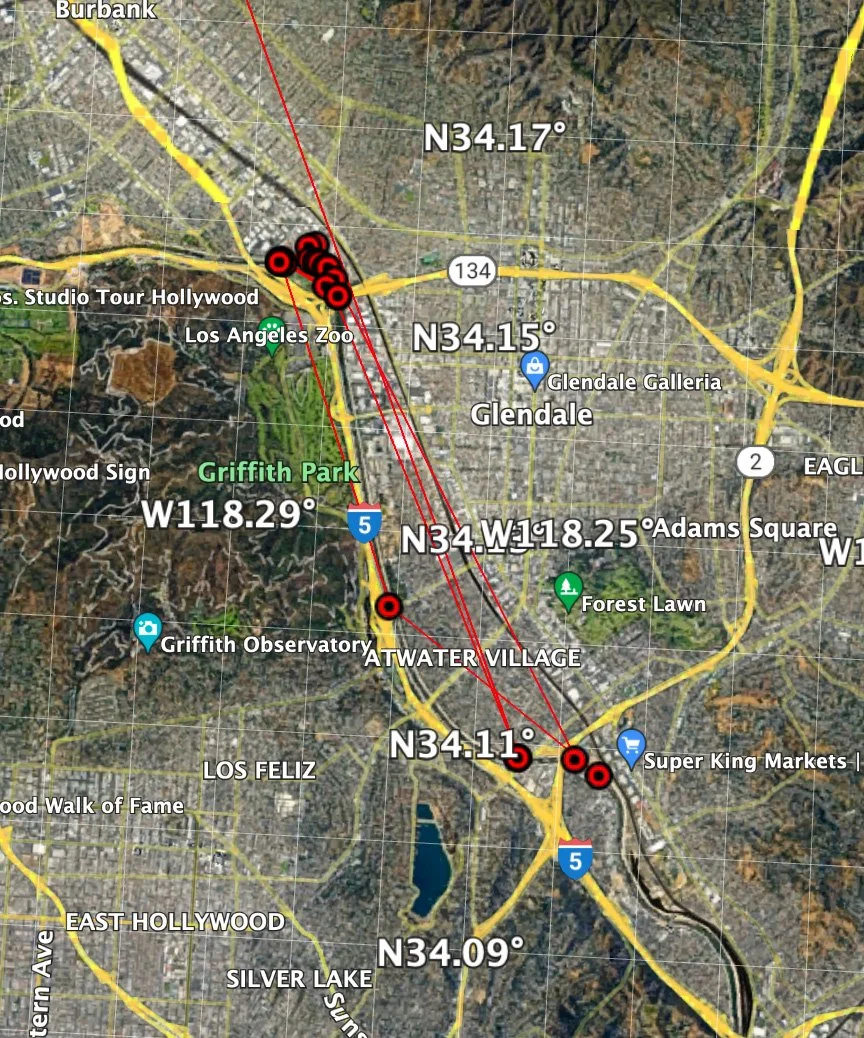

On August 10th, it touched down on the Los Angeles River, where its been for nearly a month - using the Elysian Valley and, more heavily, the bend in the river where 134 and 5 meet, alongside the John Ferraro Athletic fields and Griffith Dog Park.

Locations are taken every two days and are uploaded to satellites every six days - so there is a delay in transmission - but as of Sept 4, #243433 was riverside of Dreamworks Studio, at 34.1563759, -118.285988. Look for a metal band and a thin, long antennae extending past the rump.

Nearly all the other tracked birds in #243433’s cohort have pushed farther south to wintering sites along the mainland Mexico’s west coast - where this bird may continue to. For now, it’s demonstrating, by its month-long tenure in central LA - how important and resource-rich fragments of foraging habitat in heavily urban areas is.

Rozy Bathrick is a PhD Student in Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at UMass Amherst. Follow her on Twitter at @rozybathrick.